Turkish Militaria in the Light of Exhibitions of 1983

| ARTICLE | |

|

Turkish Militaria in the Light of Exhibitions of 1983 (written in 1983 on the 300th Anniversary of Vienna battle) by Zdzislaw Zygulski jun.

|

The Siege and Relief of Vienna 1683 have left a permanent mark in the historical consciousness of several nations, which is proved by periodical jubilees of these events, particularly magnificent in last year. The victory of allied forces, of Austrian, German and Polish troops, under the highest command of the Polish King Jan III Sobieski, at the foreground of the Imperial capital, on 12 September, 300 years ago, put an end to the long-lasting aggression of Ottoman State, directed to the very heart of Europe. Without any exaggeration one can state that the Battle of Vienna, and some following victories won by the Holy League, ending with the Treaty of Carlowitz in 1699, have founded a new balance of European powers, much increasing the importance of Habsburg Empire, of Prussia and Russia. Soon the Mediterranean, free of the galleys with Crescent, stood open for the expansion of some European countries to the Near East.

The recent jubilee has brought a lot of new historical publications, mainly in German, but also in Polish and other languages, it was also conspicuous by some major museum exhibitions, especially in Vienna and in Cracow. One significant feature of this jubilee was, rather unexpected, interest from the part of Turkey. Of course it had no masochistic background but strictly scholarly inquisitiveness concentrated on many Turkish objects which were reminded and again put into light. On the other hand it was not by mere chance that at the same time a grandiose exhibition of the “Anatolian Civilizations”, with the support of the Council of Europe, was arranged in Istanbul. This was a really huge show consisting of various sections, located in various places all over the city, with the most important part in the grounds of the Topkapi Sarayi.

It is quite obvious that in all Vienna Siege and Relief exhibitions militaria of both fighting sides played a substantial role, however it should be explained that each „side” was differentiated, being put together with various nationalities distinguished by traditional wear, weapons and combat habits. Among Christians Polish soldiers differed from Austrian and German ones, and the same can be said about Tartar, Walachian, Moldavian, Hungarian, Serbian, Albanian, and even Iraqui, Syrian and Egyptian troops serving as vassals for the Ottoman Sultan. This is a basic statement when one wishes to approach problems of the „Turkish arms”. „Turkish” is often substituted with „Ottoman” but it is not the same. More correctly „Turkish” in the 15—19th centuries meant „Anatolian”. We use here the term „militaria” because we are dealing here not only with arms and armour but also with equipment, especially equestrian equipment, with insignia, with military iconography, plans, reports, diaries and letters.

Before all it seems to be wiseful to sketch in few lines a topography of Turkish militaria in present collections. It is quite clear that the richest bulk of these items have been preserved in contemporary Republic of Turkey, despite of the fact that since the 17th century a great number of objects were destroyed in that country or taken abroad as gifts or to be sold, especially in 19th and 20th centuries. A sort of autochthonous turcica can be found in the lands which earlier in part or totally belonged to the Ottoman Empire. Therefore Ottoman arms are now in some museums or in rare private collections in Budapest, Beograd, Sophia, Bucharest and Cairo. Besides, what is also natural, Turkish militaria, coming mainly as trophies or booty, belong to the countries being once in war against the Ottomans, as Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and Russia. The fourth group is formed by turcica collected by the countries with flourishing interest in Oriental objects, as for example France, Great Britain, Denmark, Netherland or the United States. In this domain a special position is occupied by Sweden, where several Turkish objects came as a booty from Poland in time of the Northern War, heroes of which were King Charles XII and his unfortunate enemy Augustus II Elector of Saxony, King of Poland and a heir of many trophies won by Sobieski. Of course one category does not exclude the other, particularly some new collections may be born everywhere. In general, all these items have now a museum or semi-museum status.

In comparison with a speedy progress in the field of research of Western arms and armour, the development of the study of Oriental arms (except of Japanese ones) is rather slow. This is caused partly by little activity of the Turks. A modern specialization is possible only by a close confrontation of real objects with reliable iconography, backed by written sources. Most of the archives extant in Turkey are still not investigated. In new outlines of Turkish art old arms and armour, being undeniably works of advanced craftmanship and high ornamental sensitivity, are neglected and omitted. In result some old scholars, who were busy in the field long ago, are still venerated as authorities and their opinions steadily repeated; they are, among others, J. Szendrei, H. Stocklein, Ch. Buttin, H. Moser and G. C. Stone. Stocklein was the first Westerner to investigate the Armoury of Topkapi Sarayi, and not much has been added to his statements. After 1950 the interest was concentrated upon the publishing of concise and well illustrated catalogues or short articles on important collections of Turkish militaria: this was made by Ernst Petrasch for Karlsruhe, Johannes Schobel for Dresden, Bruno Thomas and Walter Hummelberger for Vienna, Peter Jaeckel for Munch en and Ingolstadt, Zdzisław Zygulski Jr. for Cracow and Warsaw, Jurij Miller for Leningrad. A general and very accurate survey of Turkish militaria was made by Jaeckel in connection with major exhibitions: of Max Emanuel in Schleissheim (1976) and of Die Turken vor Wien, in Vienna (1983). General articles on Muslim arms appear in ,,Gladius” in Spain, of which the main motive is to expose contacts between East and West in the field of militaria, an excellent expert of Arab weapons, Abdel Rahman Zaky, belonging to the editorial staff of this periodical. The late British scholar H.Russel Robinson devoted to Turkey a chapter in his book on Oriental armour, and a Yugoslavian lady, M. Sercer, prepared an extensive study of Turkish yatagans. In present times there is only one scholar busy with these problems in Turkey: Onsel Yucel, at first tied with the Topkapi Serayi Muzesi and now with the University of Istanbul.

The exhibition „Die Türken vor Wien”, organized by the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, scholarly prepared by Robert Waissenberger and Günther Düriegl, arranged by Hans Hollein, was based on local collections but also on numerous loans from abroad6. The largest loan came from Cracow: National Museum and State Collection of Art in the Wawel, with a magnificent Zulfikar banner, a tent, two full armours of sipahi, and two rich saddles, trappings and caparisons. From the Vienna Arsenal the city museum inherited a good portion of Turkish booty, but far from possibility for adequate representation of the Ottoman army. Vienna is really rich in Turkish battle sabres and lances, banners of lower rank (bayrak) and horse-tail standards. The set of sipahi lances (unfortunately without pennons) is second only to the Topkapi Museum. Three objects in the Vienna exhibition, apart from things from Cracow, were of extraordinary value: a tent of crimson brocaded silk, the saddle attributed to Kara Mustapha (Kunsthistorisches Museum) and the mail armour of janissary aga Mustapha Pasha from Karlsruhe. In the catalogue militaria were put in one chapter „Die Waffen der Osma-nen”, with reliable descriptions of every object; in the exhibition, however, this material was divided into several rooms. The principal hall was transformed into the battlefield with ranks of Christian infantry (represented by helmets, cuirasses, pikes and muskets), with cavalry of Polish allies, and Turkish cavalry- on dummy-horses, some of them in peculiar poses. Son et lumiere effects were introduced into this hall. Hollein’s idea was to achieve a maximum of expression, which was accentuated by dressing of the old venerated facade of the Wiener Künstlerhaus, where the main part of exhibition took place, into a Turkish tent, with plastic figures of the grand vizier and janissaries shooting down with arrows. The including into the show of some pieces of the 19th century iconography of the battle did not add to the clarity of Ottoman army fighting at Vienna. The role of integration and elucidation was given to dioramas of figurines representing various episodes of the siege and relief of Vienna, displayed in a separate room, works of Polish and Austrian amateur and professional model makers. A historical diorama is always based on results of scholarly research but it also reflects artistic talents, intuition, or even a mere fantasy of the maker. Dioramas made usually for didactic purposes are not free of misinformation, schematic repetition and even infantilism. The dioramas of the Vienna show were very carefully done and pretty attractive but not without the mentioned vices. They showed the Ottoman army without allied colourful troops, without Tartars, without Arnauten guards of the grand vizier.

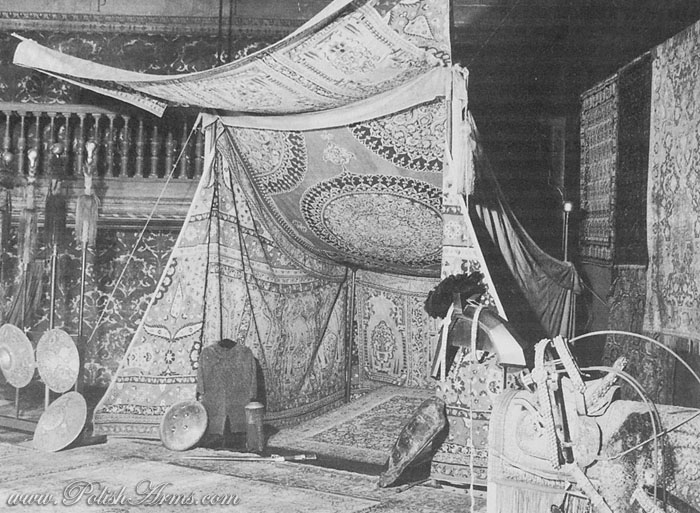

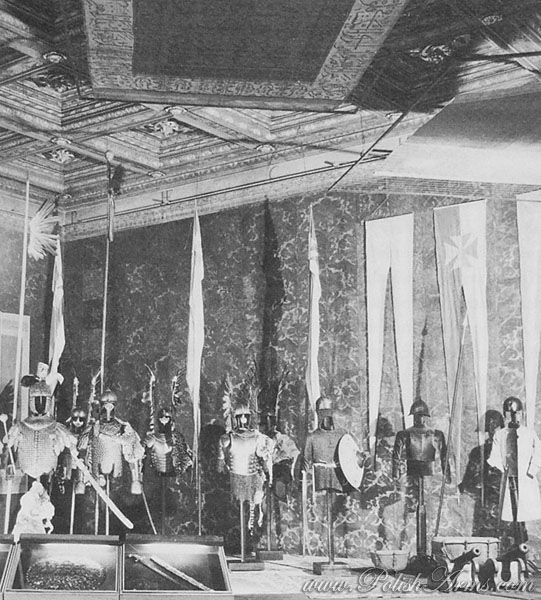

Expressionistic features dominated also the exhibition „Vienna Siege 1683″ arranged in 1983 in the Royal Castle of Wawel in Cracow, with cooperation of the National Museum of Cracow, under the direction of Jerzy Szablowski and Zdzisław Zygulski Jr., according to the artistic project of Mr and Mrs Wajda. There is no question that temporal and occasional exhibitions prepared for a large public must speak with a very special language. As for the Turkish militaria almost entirely local material was used in Cracow. In this matter loans outside were limited to a banner from Dresden and some battle-piece pictures from Munich and Budapest. A suite of splendid rooms of the Castle enabled a consistent set of problems. In the introductory hall the rapid growth of the Ottoman Empire was shown by the monumental canvas “The Entry of Mehmed II to Constantinople” painted by Stanislas Chlebowski, a court painter of Sultan Abdulaziz in Istanbul. A group of Turkish armours and arms, from the 15th-17th centuries, with a horse armour and five tail-standards, „rode out” fromthe picture (picture 1). Successive rooms were devoted to the history of warfare between Poland and Turkey, showing important battles, their heroes and weapons, documents and plans. A separate place was given to Sobieski and his family, and another one was to show diplomatic activities preceding the war of 1683. The final room, one of the biggest in the Castle, known as the Senators’ Hall, was changed (like in Vienna Künstlerhaus) into the battlefield, with an open ceremonial tent and five horse-tail standards (tug), with five enormous banners suspended from the roof, with numerous Turkish arms, armours and saddles, magnificent rugs and hangings, with personal things of the grand vizier, his sabre and stirrup (which was sent by Sobieski to the Queen Maria Casimira as a sign of victory), (picture 2). On the other side a splendid group of armours represented victors. There were among others: the karacena scalearmour of King Sobieski (a loan from Dresdner Rüstkammer) and karacenas of hetmans: Jabłonowski and Sieniawski, co-commanding in the battle, armours of winged hussars and mail suits for the medium-cavalry, also armaments of infantry (picture 3). All these objects are well documented and there is no doubt about their origin. Many of Turkish militaria reached our times as vota in churches or monasteries, particularly in the famous Mons Clara, monastery of Paulines at Częstochowa (Tschenstochau). Numerous saddles, saddle-cloths, armguards, kalkan-shields, bows, quivers, arrows and jerids belong to the Czartoryski Collection of the National Museum in Cracow, inherited by the Czartoryski from hetman Sieniawski. These objects were exhibited in the first Polish national museum: the Sibyl’s Temple at Puławy, the old residence of the Czartoryski, opended to the public as early as 1801.

In the Wawel show, out of the Senators’ Hall the path led to the rooms of permanent display of five huge Turkish tents, of applique work, having a certified Vienna tradition. One could enter and pass all these tents, and this was the moment of gradually diminishing emotions which had been kindled to an acme in the preceding hall.

No matter how magnificent and spectacular was the Wawel exhibition of 1983, it did not deepen the knowledge of Turkish militaria survived in Polish hands. No new items were brought into light, as they were, for instance, in the field of textiles. Arms, armour and insignia, especially banners, were known from earlier researches and publications. Besides, they could not have been compared with a similar material from abroad, because there were no objects from outside Poland (except of the mentioned Dresden banner). The catalogue of the Wawel exhibition has not been printed in time, nevertheless there was no place in it for a special dissertation on Turkish militaria.

There is little doubt that the future progress in the study of Turkish militaria depends on a more vivid activity of Turkish scholars: only a fortunate combination of rich collection of original objects, of their correct image in pictures and their description in documents can assure a true knowledge. There is still another important factor: in any human creation there are subtleties which may be explained only by the maker or by his countrymen. Anyway it seems to be wiseful at the end to look at the exhibitions of militaria in Turkey just in the year 1983 when so much interest was paid to the history of that country.

In Turkey old weapons are preserved mainly in Istanbul. Few objects of that kind in the Ethnographical Museum in Ankara and in some provincial museums have no importance for theoretical research tending to a synthesis. One can trace the origin of Turkish military museums back to early days of Ottoman Sultans, when weapons and instruments of war were assembled in their treasuries at Yenisehir, Bursa and Edirne but the most famous was the arsenal established by Mehmed II after the conquest of Constantinople in the old Byzantine church of St. Irene, which also became a storehouse of trophies. Already in 1726 this arsenal was transformed in a sort of military museum known as Dar-ul Esliha. Partly demolished in time of the abolition of the Corps of Janissaries in 1826 this museum was rearranged under the reign of Sultan Abdulmedjid and divided into two sections: Collection of Antique Weapons and Archaeological Museum, the latter being brought later to the Tiled Pavilion of the Sarayi. At that period Fetih Pasha, the grand master of artillery, ordered to make 143 figures in natural size, fully clad and equipped, representing official court and military costumes from the time of Sultan Osman, the founder of the Ottoman state, till Sultan Abdulmedjid. These figures were arranged in 31 groups of courtiers and dignitaries, of officers and soldiers, including various types and ranks of janissaries. They were really impressive and being a long way in advance of our epoch, in which museum dummies are so highly appreciated. Of course the quality of these manikins was dependent of the state of knowledge of their makers. Worn and grown old (as in this manikins share the fate of living men) they still exist in the present military museum in Istanbul. For a long time this museum known as Muse-i Askeri Humayun (The Imperial Military Museum) was located in St. Irene, much developed under Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909) thanks to the activity of its director Mukhtar Pasha. All over the Empire he penetrated storehouses and military barracks looking for old weaponry and other military items. According to the dominating rules of display, particularly the rule of horror vacui, exhibits were gathered in panoplies or crowded in vitrines – their quantity being the main expressive factor. In such a state thousands and thousands miscellaneous items of weaponry survived till the outbreak of World War II, when for safeguarding they were transferred to Nigde in Central Anatolia. Back in Istanbul in 1945 they were deposited in the building of the Military Gymnasium in Harbiye which finally was adopted for new purposes and as Askeri Muse opened to public in 1959. In this the system of panoplies and of a great crowding of heterogenic objects, a mixture of old with modern ones, and extra fine with mediocre or poor has been maintained. There is however a project to construct on the very place a new building to house the Military Museum and a Culture Centre. A special exhibition of tents was organized in 1983 by the Askeri Muse. Some scores of tent fragments from the 17th till 19th centuries, a complete military tent and an imperial tent Otag-i Humayun, of crimson cloth embroidered with gold, coming from the 19th century, were displayed in a separate pavilion. But none of these exhibits could match the splendour of 17th century tents captured at Vienna in 1683, of which some pieces survived in Cracow, Vienna and Stockholm.

The Askeri Miize is supplemented by the Deniz Müzesi – The Naval Museum of Istanbul which, originally established in Kasimpasha in 1897, in 1949 was moved to the Dolmabahce Mosque and finally in 1961 to the former Finance Building in Besiktas. There are gathered objects documenting great days of the imperial fleet, especially from the 16th and 17th centuries: clothes worn by sailors, banners, guns and other naval weapons, models of ships, pictures and maps. A quite unique specimen is the galley of Sultan Mehmed IV. There is also a Turkish banner from the Lepanto battle (1571) captured by Christians, kept for a long time in Italy, and given back to Turkey by Pope Paul VI in 1975.

A very important and valuable collection of Turkish (and not only Turkish) arms is housed in the Topkapi Sarayi Müzesi in an old building, probably constructed in times of Sultan Mehmed II, called Ichazine (The Inner Treasure) with eight domes resting on three large central pillars (here originally was stored the money nened-ed for use in the Hall of the Divan, including that paid out to the janissaries). The hall is decorated with a superb set of horsetail standards, there is also a large collection of swords, sabres, bows, lances, battle-axes, maces, kalkan-shields, hetmets and armours. Some pieces are connected with sultans and high commanders, but in general it is not fully classified. Still in two other places of Topkapi there are pieces of excellent arms. In the main Treasury (Hazine) the attention is turned by some personal armament of sultans, among others a lavishly decorated full mail armour attributed to Mustapha III (1757-1773), and the famous dagger encrusted with big esmerald, once a gift for Nadir Shah of Iran, after his death returned to Istanbul. In the very heart of the Topkapi, in the Hall of the Holy Mantle of Mahomet (Hirka-i Saadet) there is a splendid set of several swords attributed to the Prophet himself and the first caliphs, and above all there is the Holy Banner (Sanjak-i Sherif), the most venerated military relic which led Ottoman warriors to many victories. This portion of the collection, especially swords, were studied by A. R. Zaky, but in fact everything here deserves a more profound research. The special exhibition of 1983, mentioned above, The Anatolian Civilizations was a true stimulation to this. The most important part of the show was arranged in the old imperial stables, where masterpieces of Seljuk and Ottoman Art from various Turkish museums were put together. There were also some exquisite items of arms and armour: gilded zischägges, ornamented wicker shields — kalkans, and above all magnificent swords and sabres of Mehmed the Conqueror and a yatagan of incredible beauty of Suleyman the Law Giver.

It is quite obvious that the survey of Turkish militaria made in 1983 is pretty promising and encouraging for future studies.